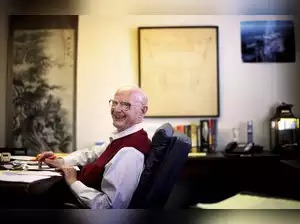

Harry M. Markowitz, an economist who launched a revolution in finance, upending traditional thinking about buying stocks and earning the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1990 for his breakthrough, died Thursday in San Diego. He was 95.

The death, at a hospital, was caused by pneumonia and sepsis, Mary McDonald, a longtime assistant to Markowitz, said.

Until Markowitz came along, the investment world assumed that the best stock-market strategy was simply to choose the shares of a group of companies that were thought to have the best prospects.

But in 1952, he published his dissertation, “Portfolio Selection,” which overturned this common-sense approach with what became known as modern portfolio theory, widely referred to as MPT.

The heart of his research was grounded in the basic relationship between risk and reward. He showed that the risk in any portfolio is less dependent on the riskiness of its component stocks and other assets than how they relate to one another. It was the first time that the benefits of diversification had been codified and quantified, using advanced mathematics to calculate correlations and variations from the mean.

This breakthrough insight and its corollaries have now permeated all aspects of money management, with few professionals unfamiliar with his work.

“Modern portfolio theory has gone from the halls of academia to investment management mainstream, or from gown to town,” Robert Arnott, CEO of Research Associates, a large investment manager in Newport Beach, California, said in a videotaped interview with Markowitz.

When Markowitz heard one of his peers describe how his work had brought “a process” to what had been, until the 1950s, the “haphazard” creation of institutional portfolios, he knew he deserved his reputation as the father of modern portfolio theory, he said.

“That moment was one of these things where you feel a chill run up your spine,” he said. “I understood what I had started.”

In 1999, the financial newspaper Pensions & Investments named him “man of the century.”

Related work on investments led Markowitz to be regarded as a pioneer of behavioral finance, the study of how people make choices in practical situations, as in buying insurance or lottery tickets.

Recognizing that the pain of loss typically exceeds the joy of comparable gain, he found it crucial to know how a gamble is framed in terms of possible outcomes and the size of the stakes.

Markowitz won renown in two other fields. He developed “sparse matrix” techniques for solving very large mathematical optimization problems — techniques that are now standard in production software for optimization programs. And he designed and supervised the development of Simscript, which is used for programming computer simulations of systems like factories, transportation and communications networks.

In 1989 Markowitz received the John von Neumann Theory Prize from the Operations Resesearch Society of America for his work in portfolio theory, sparse matrix techniques and Simscript.

His focus was always on applying mathematics and computers to practical problems, particularly involving business in uncertain conditions.

“I’m not a one-shot Nobel laureate — only doing one thing,” Markowitz said in an interview for this obituary in 2014. Although he was 87 at the time, he was embarked on a monumental analysis of securities risk and return.

The seminal 1952 paper, in The Journal of Finance, was expanded into his best-known work, “Portfolio Selection: Efficient Diversification of Investments,” in 1959.

Harry Max Markowitz was born on Aug. 24, 1927, in Chicago, the only child of Morris and Mildred Markowitz, who owned a small grocery store.